Dimensionality Reduction

This post focuses on the mathematical underpinnings of dimensionality reduction from a projection-optimization point of view and raw numpy implementations.

Set-Up

Setting: Have a dataset \(D \in R^{n*d}\) i.e

\[D = \begin{bmatrix}x_{11} & x_{12} & \dots & x_{1d}\\\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ x_{n1} & x_{n2} & \dots & x_{nd} \end{bmatrix}\]where each row is a vector in a \(d\)-dimensional cartesian coordinate space, \(x_i \in R^d\) i.e \(x_i = (x_{i1},x_{i2},x_{i3},...x_{id})^T \forall i \in \{1...n\}\) and each row is spanned by ‘\(d\)’ standard basis vectors i.e \(e_1,e_2...e_d\) where \(e_j\) corresponds to the jth predictor \(\in D\) i.e the jth standard basis vector \(e_j\) is the d-dimensional unit vector whose jth component is 1 and the rest of the components are 0, \(e_j = (0,...1,...0)\).

Since it is a standard basis, we observe two interesting properties:

\[i.) \ e_i^T.e_j = 0 \ \forall \ i,j \ni i\neq j \\ ii.) \ ||e_i|| = 1\]Now, given any other set of \(d\)-orthonormal vectors \(\{u_1,u_2,...,u_d\}\) we can express each row \(x_i \forall \ i \in \{1,2,...,n\}\), which can also be thought of as a point in a \(d\)-dimensional space, as a linear combination of the new \(d\)-orthonormal vectors and some constant vector \(a = (a_1,a_2,...,a_d)^T\). In matrix form,

\(x = Ua\) where \(U \in R^{d*d}, a \in R^d\).

Note that, U is a diagonal matrix since it comprises of d-dimensional unit vectors which have a value of 1 corresponding to the jth predictor and 0 otherwise.

Key Questions: There are some natural questions to ask in regards to the above setting:

K1. As there are infinite choices for the set of orthonormal basis vectors, can we somehow select an optimal basis?

K2. If \(d\) is very large can we find a subspace of \(d\) such that essential charecterstics of data are still preserved?

Asking these questions stem the notion of dimensionality reduction.

Formally, the objective with dimensionality reduction is to seek an \(r\) dimensional basis \(\ni r << d\) that gives the best approximation of the projection of all points \(x_i \in D\) on \(x_i' \in A\) where \(A\) is the r-dimensional subspace of D. This can alternatively be viewed as minimizing \(\epsilon = x_i-x_i'\) over all \(x_i \forall i \in \{1,2...,n\}\)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Idea: The basic idea is to project points from our Dataset \(D\) onto a lower dimensional subspace \(A\) in such a way that we still capture most of the variation in our data (This answer’s K2).

1. Project points from D onto the subspace with a basis denoted by U.

\[x_i = Proj_{subspace}x_i + Proj_{subspace}^{\perp}x_i \\ x_i = C(U) + C(U)^{\perp} = C(U) + N(U^{\perp}) = C(U) + 0 \\ \implies x_i = Ua\]This makes intuitive sense sense as any point in the projected subspace should be reachable as a linear combination of the basis vectors and some constants.

We can solve for a as follows,

\[x_i - Ua = 0 \\ U^Tx_i - U^TUa = 0 \\ \implies a = U^Tx_i(U^TU)^{-1} \\ \implies a = U^Tx_i\]The above ‘a’ gives coordinates of projected points in the new basis. Note that the above inverse always exists as U being a orthogonal matrix is linearly independent and non-singular. Furthermore, since U is orthogonal, \(U^{-1} = U^T \implies U^TU = I\)

2. Look at the variance of projected points along the subspace.

Assuming a 1-D subspace.

\(\sigma^2_u = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n(a_i - \mu_u)^2 \\\) \(\mu_u = 0\) if we center the data. \(\sigma^2_u = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n(a_i)^2 \\ = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n(u^Tx_i)^2 \\ = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n(u^T(x_ix_i^T)u) \\ = u^T (\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_ix_i^T) u \\ = u^T\Sigma u\)

where \(\Sigma\) is the covariance matrix of the centered data.

3. (An answer to K1): One way to select an optimum basis among all basis would be to choose a basis that maximizes the projected variance.

The above statement is super intuitive. Since, we want to find a low dimensional representation of our dataset in such a way that we still capture most of the variation in our data, it makes sense to choose a basis that maximizes the variance of this projection.

We can set this up as an equality constrained optimization problem as follows:

\[Max \ u^T\Sigma u \\ s.t \ u^Tu = 1 \\\]Using Langrange multipliers we can rewrite this constrained optimization problem into an unconstrained one and solve it.

\[Max \ u^T\Sigma u - \lambda(u^Tu - 1) \\ \frac{\partial u^T\Sigma u - \lambda(u^Tu - 1)}{\partial u} = 0 \\ 2\Sigma u - 2\lambda u = 0 \\ \implies \Sigma u = \lambda u\]The above result is very profound, it basically means that the langrange multiplier ‘\(\lambda\)’ is actually the eigenvalue of the covariance matrix ‘\(\Sigma\)’ with an assosiated eigenvector ‘\(u\)’.

Now, taking a dot product with \(u^T\) on both sides we get

\[u^T\Sigma u = u^T\lambda u \\ Since, \ \sigma^2_u = u^T\Sigma u \\ \implies \sigma^2_u = u^T\lambda u \\ \implies \sigma^2_u = \lambda\]This means that, to maximize the projected variance along basis ‘\(u\)’ we can simply choose the largest eigenvalue ‘\(\lambda_1\)‘of \(\Sigma\) and the corresponding eigenvector ‘\(u_1\)’ is the dominant eigenvector specifying the direction with the most variation and is also the known as the principal component.

Now for 2-dimensions, we find the next basis component say ‘v’ that maximizes the projected variance (\(\sigma^2_v = v^T\Sigma v\))and since the basis vectors are orthonormal by definition we have an additional constraint in our optimization problem \(u^Tv = 0\).

\[Max \ v^T\Sigma v \\ s.t: \ i.) \ v^Tv = 1 \\ ii.) \ u^Tv = 0 \\\]Using Langrange multipliers we can rewrite the optimization problem into an unconstrained one as:

\[v^T\Sigma v - \lambda(v^Tv - 1) + \beta(u^Tv) = 0\]Taking \(\frac{\partial}{\partial v}\) we get,

\[2\Sigma v - 2\lambda v - \beta u = 0\]Multiplying with \(u^T\) and solving for \(\beta\) we get:

\[\beta = 2v^T \Sigma u = 2\Sigma v^Tu = 0\]Sub \(\beta\) in the unconstrained objective function we get,

\[v^T\Sigma v - \lambda(v^Tv - 1) = 0 \\ \implies \Sigma v = \lambda v\]Now, this time to maximize the projected variance (\(\sigma^2_v\)) along basis ‘\(v\)’ we need to choose the second largest eigenvalue ‘\(\lambda_2\)‘of \(\Sigma\) and the corresponding eigenvector ‘\(u_2\)’ specifies the direction with the most variation and is known as the second principal component.

It is pretty straight forward to extend the same notion to an r-dimensional case.

Assuming we have already computed \(j-1\) principal components. The jth new basis vector that we would like to compute say ‘\(w\)’ would naturally be orthogonal to all previous components \(u_i \forall i \in \{1,2...,j-1\}\) by construction.

Therefore, this is how the optimization problem would look:

\[Max \ w^T \Sigma w \\ s.t \ i.) w^Tw = 1 \\ ii.) \ u_i^Tw = 0 \ \forall \ i \in \{1,2...,j-1\}\]Rewriting the optimization problem using Langrange multipliers:

\[w^T \Sigma w - \lambda (w^Tw - 1) - \sum_{i=1}^{j-1} \beta_i (u_i^Tw)\]As earlier solving for \(\beta\) and re-substituing that in the optimization problem yields:

\[\Sigma w = \lambda w\]Now, as earlier to maximize the variance along basis ‘\(w\)’ we need to choose the jth largest eigenvalue ‘\(\lambda_j\)‘of \(\Sigma\) and the corresponding eigenvector ‘\(u_j\)’ specifies the direction with the most variation and is the jth principal component.

Understanding this optimization problem helps provide an intuition as to why computing the covariance matrix of D i.e \(\Sigma\) and picking it’s eigenvectors give us the principal components.

4. What is the total projected variance?

If we truncate the projection (\(x'\)) of \(x\) to the first \(r\)-basis vectors we get:

\[x' = U_ra_r\]where \(U_r\) represents the \(r\)-dimensional basis vector matrix. Also, from \(a = U^Tx\) we can get \(a_r = U^T_rx\). Plugging this into \(x'\) we get:

\[x' = U_rU_r^Tx = P_rx\]This \(P_r\) is the orthogonal projection matrix for the subspace spanned by the first \(r\)-basis vectors. This projection matrix can be decomposed as:

\[P_r = \sum_{i=1}^ru_iu_i^T\]Let the co-ordinates of all projected points (\(x'\)) of \(x_i \in D\) yield a new matrix \(A\) where \(a_i \in R^r\). Since, we assume \(D\) to be centered co-ordinates of the projected mean are also assumed to be 0.

Now, the total variance of \(A\) is:

\[var (A) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n||a_i - 0||^2 \\ = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n(U^T_rx_i)^T(U^T_rx_i) \\ = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^T(U_rU_r^T)x_i \\ = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^TP_rx_i \\ = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^T(\sum_{i=1}^ru_iu_i^T)x_i \\ = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_ix_i^T(\sum_{i=1}^ru_iu_i^T) \\ = \sum_{i=1}^r u_i^T\Sigma u_i\]Since, \(u_1,u_2,...u_r\) are eigenvectors of \(\Sigma\) we have \(\Sigma u_1 = \lambda u_1, \Sigma u_2 = \lambda u_2, ..., \Sigma u_r = \lambda u_r\). Therefore,

\[var (A) = \sum_{i=1}^r u_i^T\Sigma u_i = \sum_{i=1}^r u_i^T\lambda_i u_i = \sum_{i=1}^r \lambda_i\]Therefore, total variance of the projection is the sum of the \(r\)-eigenvalues of the covariance matrix (\(\Sigma\)) of D.

5. How many principal components to choose?

Given a certain threshold for the amount of variance to be explained say \(\gamma\) we need to choose the cardinality of \(r\) such that the ratio

\[\frac{Var(A)}{Var(D)} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^r \lambda_i}{\sum_{i=1}^d \lambda_i} \geq \gamma\]Python implementation

Implementing this algorithm is pretty straight forward. All we need to do is:

i.) Center D and find it’s covariance matrix \(\Sigma\).

ii.) Compute eigenvalue, eigenvector pairs and sort the eigenvalues in descending order.

iii.) Pick the PC’s that give the required variance.

iv.) Use their corresponding eigenvector forming the reduced basis to compute the Reduced Matrix.

Our Implementation:

def PCA(data,threshold):

'''Takes in a dataset and a specified threshold value to return a low dimensional representation

of the original dataset containing threshold % variance of the original dataset'''

start = time.time()

data2 = np.matrix(data)

#Compute mean

mu = data2.mean(axis = 0)

#center the data

data2 = data2 - mu

#compute covariance matrix

cov = (1/data2.shape[1])*(data2.transpose()*data2)

#Compute eigenvalues

eig_val, eig_vec = np.linalg.eig(cov)

#Sort eigenvalue, eigenvector pairs

eig_pairs = [(np.abs(eig_val[i]), eig_vec[:,i]) for i in range(len(eig_val))]

eig_pairs.sort(key=lambda x: x[0], reverse=True)

eig_val_sort = list(np.flip(np.sort(eig_val)))

#Number of principal components needed

for i in range(len(eig_val)):

check = sum(eig_val_sort[0:i])/sum(eig_val_sort)

if check >= threshold:

print('Number of principal components needed: ', i)

number_pc = i

break

else:

i +=1

#Ratio of variance explained

var_explained = [i[0]/sum(eig_val) for i in eig_pairs[0:number_pc]]

#Basis of the selected PC's

basis = [i[1] for i in eig_pairs[0:number_pc]]

#Basis Matrix of the selected subspace

reduced_basis_mat = np.vstack((basis[0].reshape(len(eig_val),1)))

for j in range(1, number_pc):

reduced_basis_mat = np.hstack((reduced_basis_mat, basis[j].reshape(len(eig_val),1)))

#Reduced Matrix

reduced_mat = (reduced_basis_mat.transpose()*data2.transpose()).transpose()

finish = time.time()

print("Run Time: ", round(finish - start,2), "seconds")

return(reduced_mat, var_explained)

Comparision with sklearn’s implementation:

Below is a quick test of our implementation with Sklearn’s implementation. For this example we use the SECOM dataset from here.

First we load the data, drop the response and time columns. Use a simple heuristic to replace the missing values with the columns means. The dataset is now \(\in R^{1567*590}\).

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import os

import time

#Reading the data in

os.getcwd()

os.chdir('/Users/apple/Documents/ML_Data')

data = pd.read_csv('uci-secom.csv')

print(data.head(5))

#Removing Time and target variable

data.drop(columns = ['Time','Pass/Fail'], inplace = True)

#Replacing all the null values with columns mean

data.fillna(data.mean(), inplace = True)

print('Number of null values in the dataframe: ',sum(data.isna().sum()))

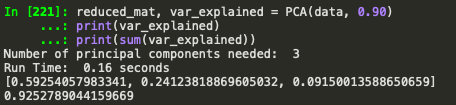

Output of our function:

reduced_mat, var_explained = PCA(data, 0.90)

print(var_explained)

print(sum(var_explained))

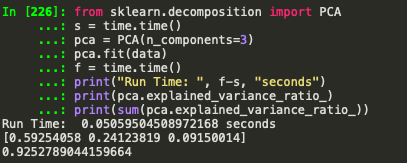

Implemtation from sklearn:

#sklearn implementation

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

s = time.time()

pca = PCA(n_components=3)

pca.fit(data)

f = time.time()

print("Run Time: ", f-s, "seconds")

print(pca.explained_variance_ratio_)

print(sum(pca.explained_variance_ratio_))

Ignoring the embarrassingly slow run time (because this was a basic implementation without vectorization or any sort of optimization) ratio of variance and total variance explained are exactly the same upto 15 decimal places. Not bad.

print(reduced_mat.shape)

The reduced matrix is in \(\in R^{1567*3}\) and explains 90% of the variance in the original dataset. This means the original high-dimensional dataset was very noisy and most of the information was only spread along a few directions.

References

MJ Zaki, W Meira Jr (2014). Data Mining and Analysis: Fundamental Concepts and Algorithms.